As we reach exactly a week into the MLB season proper, a couple storylines caught my attention because I’m not convinced the consensus presentation and digestion of either holds up under examination. We will attempt to summarize that consensus without resorting to straw men, which we abhor and properly viewed should be the province only of noble farmers, scurvy politicians and hot takesmen.

The Rafael Devers saga has been well plowed by the internet over the last couple months. The tl;dr: Boston signed an expensive free agent in Alex Bregman, who also happens to field Devers’ position much better than Raffy does. The team wanted Devers to move to full time DH, he didn’t want to initially, finally capitulated, and has performed poorly in the season’s first week. The most common fan reactions we’ve seen go something like:

Devers is not a team player, he’s pouting instead of performing, and he should do whatever the team asks!

While this sentiment is not surprising or unexpected, perhaps it is not entirely fair. Devers’ performance especially may be more influenced by the adjustment to his new role, which any recent full time fielder might endure, than by being so hurt or pissed off that he’s consciously or unconsciously sabotaging himself or his team.

Devers, the Red Sox’s $313.5 million foundational star, fell behind in his preparation this offseason due to lingering shoulder inflammation—both shoulders, actually—which caused him to see action in only three spring training games.

While his bat has always been messianic, Devers is also the worst regular third base defender in the majors and it’s not especially close: over the last four seasons Devers’ -37 Defensive Runs Saved is second lowest (Bohm, -40) and his Statcast outs above average of -29 is miles worse than anyone else.

In early February the Sox signed Alex Bregman, who had just won the AL Gold Glove at Devers’ position. A few days after the signing was announced, Devers adamantly stated he wanted to play third. We learned that Sox brass met with him but only after they had agreed to terms with Bregman.

At the time Devers made that statement, Cora told the media they would consider all options and of course stressed it was all about the team. He mentioned Bregman at third or maybe second, Devers at third or maybe DH. He framed it as “a competition” designed to make the team better—as teams are wont to frame things like this.

The interwebz exploded with speculation throughout. Bregman might play second base, a position of relative weakness (before the full emergence of Kristian Campbell). Perhaps Bregman would play third and Raffy moved to first, with promising young first baseman Triston Casas shipped out for pitching reinforcements. Roster Resource likely set page view records as projected lineups were made and tweaked and tweeted and trashed in the weeks following the Bregman signing.

Then, lo’ and behold, after a couple weeks of vague hemming and hawing, in an announcement that shocked nobody who was paying attention, Boston brass said Bregman would play third base. They also reaffirmed their commitment to Casas, shooting down the sundry trade rumors (which invariably involved the Mariners and Bryan Woo or Bryce Miller). Of course the decision was made easier by Devers’ shoulders, which kept him from participating in fielding drills at any position this spring.

Devers is, hmm, shall we say, a larger, slower moving man, making outfield or middle infield implausible defensive options for him. But it seemed likely all along that the team had already decided he wouldn’t play anywhere in the field.

Every transaction and statement they made presaged Devers at DH.

Then finally they said it. They wanted him to DH. Full time, full stop.

He didn’t want to.

A minor saga concerning what Devers had been promised ensued—turns out the front office had told him he’d play third base indefinitely, as the current regime admitted, but hey that was under the prior president of baseball ops, Chaim Bloom, which current leadership somewhat awkwardly cited as cover for the org going back on its word—times have changed and all that (forget that manager Alex Cora was in place the entire time).

A brief silence followed from all parties within Red Sox camp, as pandemonium roared without.

Devers finally came around.

Okay, he said, I’ll DH.

Except so far it’s not going okay. Or passable. In fact it’s going about as badly as one could imagine. Entering games Wednesday, Devers was hitting .000 with 15 strikeouts in 23 plate appearances. That’s a 68% strikeout rate. (He finally got his first two hits of the season Wednesday, without a strikeout, to raise his average to .087).

This is one of the best hitters in baseball.

Now, even great players will have five or six game stretches where they hit below .100, but the strikeouts may point to a more consequential cause than a cold start. Could it be the squeaky shoulders? It’s definitely possible, whether by directly affecting his swing or timing, or indirectly as the result of being behind in his season ramp up. We have some data to support this hypothesis. Last year Devers’ average bat speed was clocked at 72.5 mph, above average; so far this season it’s 70.5. That is last among Sox regulars in the early going (through Tuesday’s games).

But we’ve all also heard (you could hardly ignore it) that Devers must be “pouting” or pissed off or in some team-corroding mood (as fans see it).

Well, imagine you’re a three-time All Star and The Face of the Franchise: wouldn’t you be a bit chapped? Not only did the team change the terms of the mutual understanding—yes, unwritten but surely current events don’t mean we all have to be so cavalier about the value of words—they waited forever to do so, like a partner who waits and waits to call a relationship quits because the conversation is uncomfortable for them. Then basically said too bad, suck it up, be a good soldier. And of course fans, who usually default to teams over players, promptly applied pressure to Raffy in whatever measure screaming into the void on Twitter can apply.

These are human beings. Think of an analogous situation at your job; would you thrill with enthusiasm and confidence at what amounts to a demotion, even if your salary remained constant? Hey, we’re giving half your responsibilities to Frank because he’s better at them than you, but don’t take it the wrong way (is there any other way to take it?).

Baseball players are affected by psychological factors like anyone else. That’s just one part of it, however. Devers is a pro and pros don’t like to suck at the thing they are paid to do. It seems highly unlikely he is choosing to fester in resentment and fail to concentrate on hitting. Playing is often a refuge.

There’s another factor at issue, which is that the “DH tax” is real. Position players who toggle between the field and DH usually hit worse as a DH. The Ringer had a great column on this last year, which I’ve linked below.

As that piece points out, Russell Carleton of Baseball Prospectus studied DH performance and found that in general, players perform worse as DH compared to when they also play the field, until the point where one is doing it at least 75% of the time. Devers has been doing it for less than a week.

For an example of the DH tax, Yordan Alvarez—an even more gifted hitter than Devers—has been 30% better at the plate when he’s played the field (186 wRC+) than in games where he’s only the DH (156) despite spending a significant amount of time not playing the field over the last few seasons.

There is also anecdotal evidence for the DH tax. Hannah Keyser, who wrote the Ringer piece, spoke to or found quotes from Stanton, McCutcheon, Ozuna, Harper—all highly decorated as position players forced into full time DH roles for extended periods. They all said that succeeding in the switch takes an adjustment in mindset and to one’s pregame and in-game approach. There is an art to “keeping your head in the game” when you are technically not in the game half the time. Some make sure to stand on the top dugout step, pretending to be the manager. Some are the opposite, finding refuge in the clubhouse. It requires establishing a routine that works for the given player.

And time. It takes time.

By the way, Devers has a career 124 wRC+. If he were to lose 30%, he’d be a below average major league hitter. Surely the Red Sox are aware that there is real downside risk here.

Maybe Devers is injured, maybe he’s pissed, maybe he’s a bit of both. Or maybe, just maybe adjusting to being a full time DH is extremely difficult even without the further distractions of being rudely usurped from one’s perch at a lifelong position and perhaps also suddenly not trusting your bosses and also simultaneously dealing with the noise of the Beantown sports-industrial complex.

It’s not popular in popular culture right now, but we ought to give Devers some grace to figure this thing out.

Admittedly that’s tougher to do if you have him in fantasy. The best we can offer is to stick with him in deeper leagues and bench him until we see signs of life in shallower formats. I have heard analysts say they would not trade him. Almost no player should be off limits. If you can get a reasonable return—perhaps a Jordan Westburg?—I would be inclined to do it.

https://www.theringer.com/2024/03/29/mlb/mlb-designated-hitters-universal-dh-decline

***

Drake Baldwin is the Braves best hitting prospect (No. 11 overall per FanGraphs) and due to an injury (again) to starter Sean Murphy and total incompetence with the stick from backup Chadwick Tromp (who really sounds like he should be answering the clubhouse door with a silver platter and white gloves), Baldwin shot straight from AAA into Atlanta’s Opening Day lineup.

He was catching Chris Sale, the reigning NL Cy Young.

Their opponent, the Padres—a team that ran only moderately last season (50 as a team, 16th)—stole five bases without being caught. Manny Machado stole two (he had all of 11 last year). The conclusion was swift:

Drake Baldwin can’t control the running game to save his life.

That may or may not be true at the major league level. We simply do not have enough information to say. Baldwin’s scouting reports certainly emphasize his bat before his defense, but some like Chris Clegg have noted his continuing improvement behind the dish. In that opening day game, three of the five steals came while Sale was pitching, two against reliever Aaron Bummer (more unfortunate pitcher name: Bummer or Falter?).

Sale, on the other hand? Anyone who’s seen his prehistoric bird frame gather his hands into his windup, twist entirely towards first base, then turn back towards home while catapulting the ball, knows this is one of the most elaborate deliveries in the game.

That doesn’t make it necessarily long or time-consuming, but it’s the furthest thing from direct. Time to home and other factors in the pitcher’s control contribute to stolen bases allowed. Thankfully, in news that should surprise no one, Baseball Savant has a leaderboard for pitchers and their ability to control the running game.

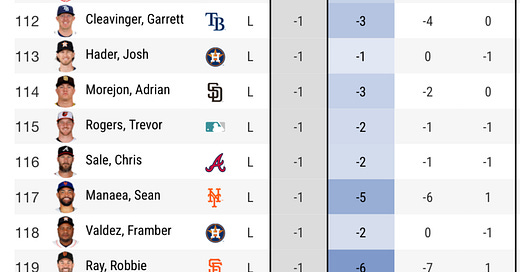

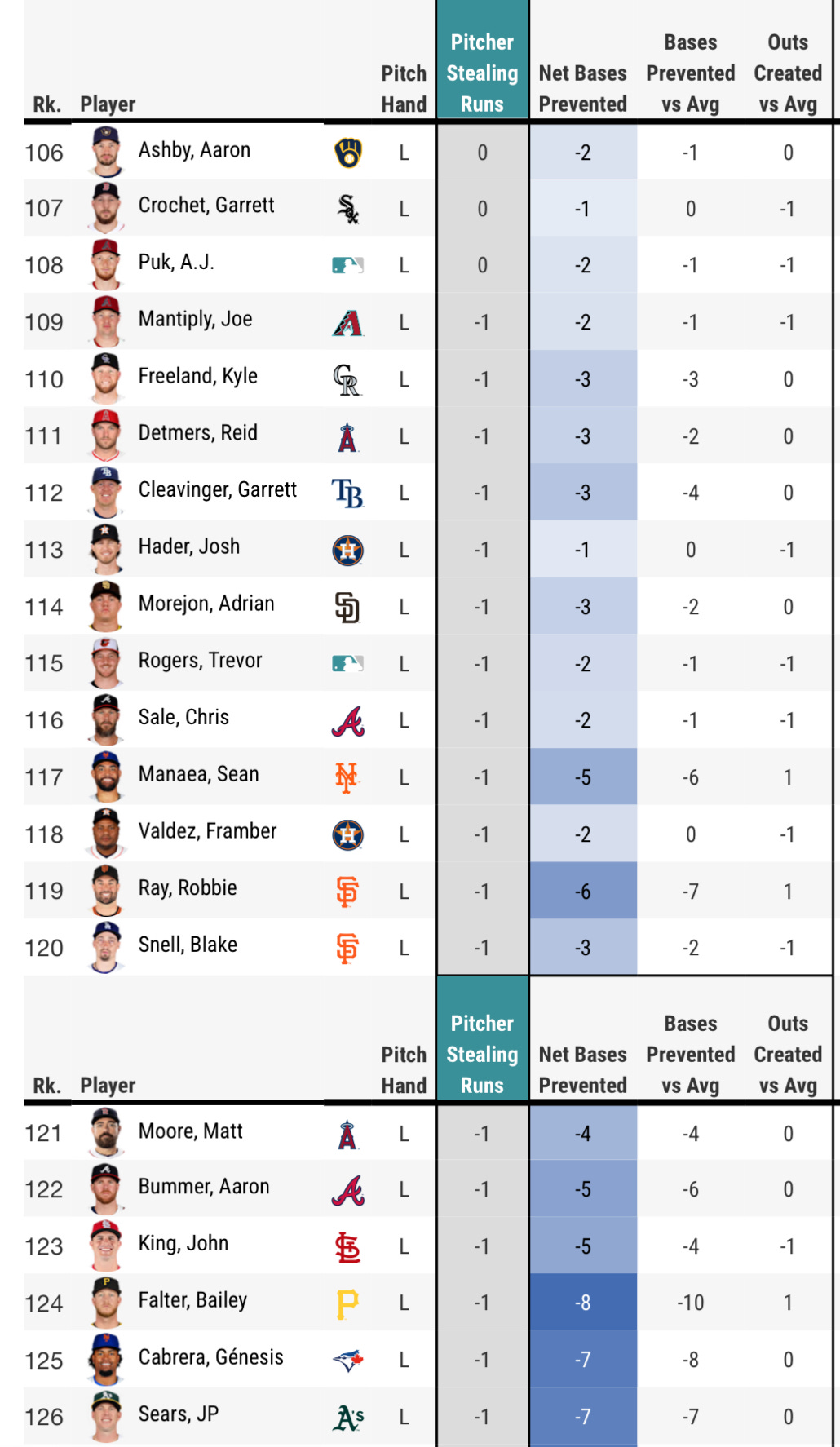

Among 131 southpaws in the database for last season, Sale ranked 116th in Pitcher Stealing Runs, a run value Savant created for “the difference between advances allowed (vs. avg) and outs created (vs. avg).”

Hey look, ranked 122nd—Bummer! So all five Padres thefts came against two bottom-16 lefties in terms of limiting steals. Perhaps their approach on Opening Day was dictated by the Braves pitchers more than by Baldwin starting behind the plate. (For fantasy and DFS purposes, note that Gore and Rodon were the worst lefty starters and Burnes the worst righty by this metric).

Baldwin started the next two games and the Padres only attempted one steal total in those contests. Then on Sunday, with Tromp starting, they successfully nabbed four more bases.

It also may be that the Padres are generally looking to increase their aggression on the base paths this season (Tatis has said as much personally in a boon to his fantasy owners).

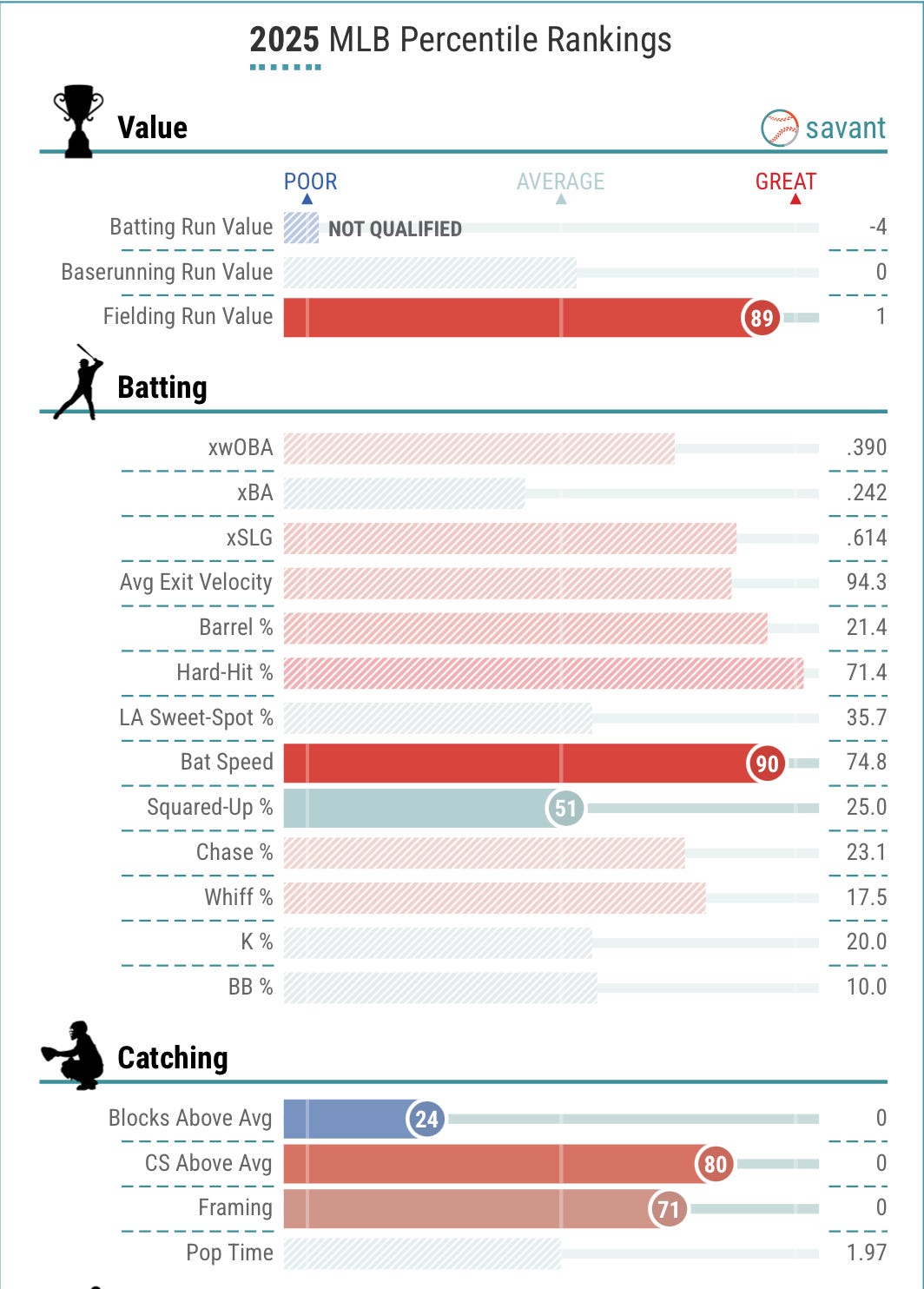

More to the point, Baldwin himself had played five games entering Wednesday. Based on his Statcast metrics, there’s no glaring issue with his pop time and certainly not with his arm:

Nor is there really an issue with Baldwin’s bat, as one can see by that Savant page, despite an early .056 batting average. He’s been crushing the ball with near-elite bat speed and well below average chase and whiff rates. This tracks with Baldwin’s metrics in AAA last year, where he posted elite quality of contact numbers (53% hard hit).

Unfortunately for him, injured starter Murphy began his rehab assignment Tuesday. Baldwin may simply run out of time for the babip and barrel gods to turn in his favor. But process wise it looks like this is a really strong hitter.

And a pretty solid fielder, or at least a player with the makings of a good one if he can improve his framing skills. The Braves know more than we do, but the fact that San Diego ran wild against Sale and Bummer doesn’t mean Baldwin can’t hack it behind the dish in the majors.